Reimagining Early Photography for Modern Interiors

Cameraless Photography

My introduction to the wonderful world of cameraless and alternative photography came when I encountered the Cyanotype process as a photography student. I was immediately intrigued by its simplicity and adaptability.

Delving into the origins of Cyanotype I discovered the work of Anna Atkins, an English botanist and photographer working in the mid 19th century. Atkins worked at a time when rigid social conventions excluded most women from scientific pursuits, or from having any kind of career at all, making her achievements all the more remarkable.

Photographic Pioneer

Not only was Atkins a respected botanist, elected to the Royal Botanical Society in 1839, she is widely credited as the first person to publish a book illustrated using photography—Photographs of British Algae, Cyanotype Impressions, 1843. In a field dominated by competitive male pioneers, how was Atkins able to become the first person to use photography to illustrate a book?

Anna Children

Born Anna Children in Kent, England, in March 1799, she tragically lost her mother, Hester Anne (née Holwell), who never fully recovered from childbirth and died at just 23.

Anna’s father John George Children was a scientist and a Fellow of the Royal Society. Among his friends were some of the most influential scientists of the day including Humphrey Davy, John Herschel and the photographic pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot.

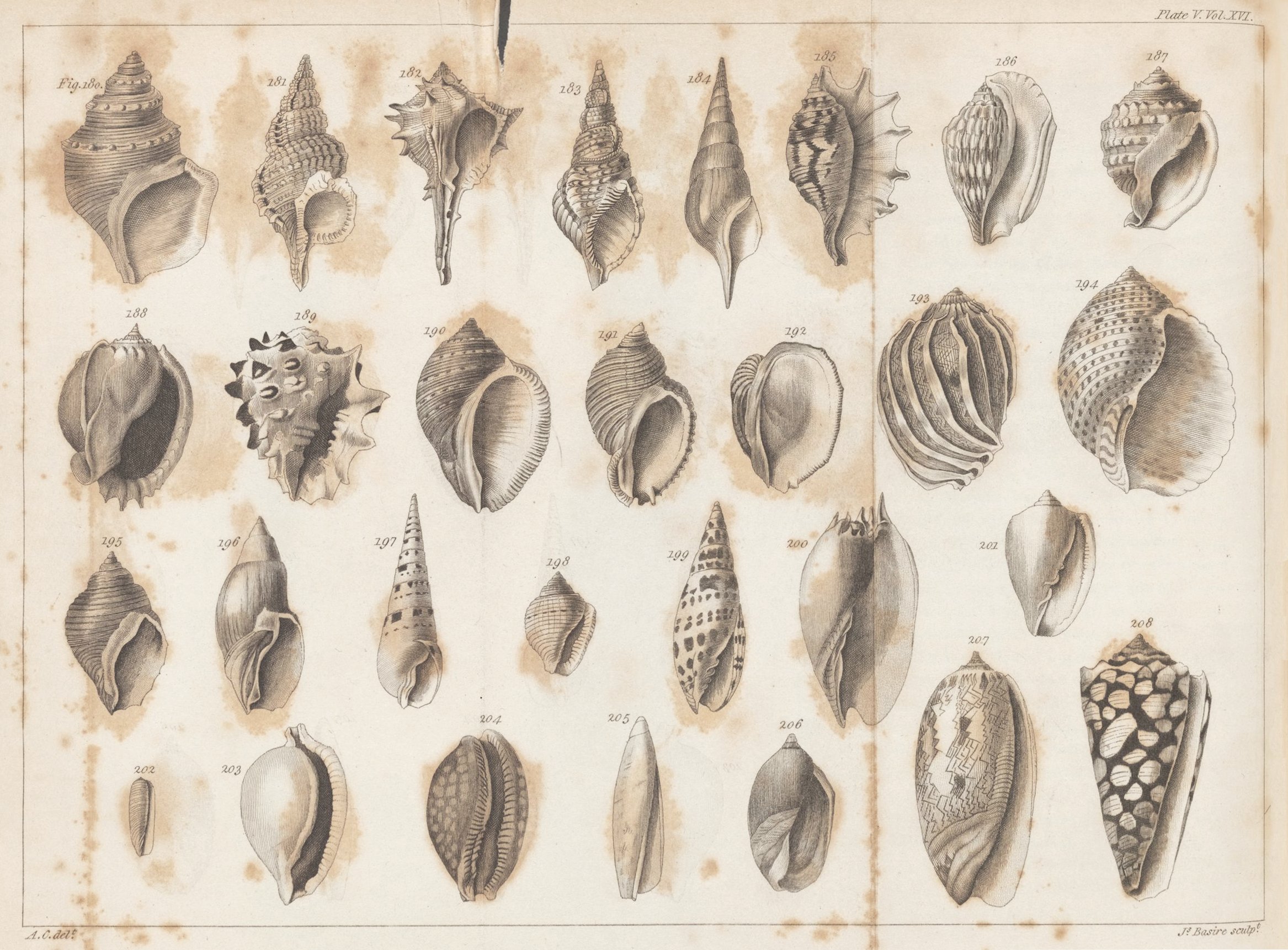

Anna and her father enjoyed a close relationship and he encouraged his daughter’s passion for nature, science and drawing. They worked together and her first major scientific contribution were illustrations used in her father’s translation of Lamarck’s Genera of Shells in 1823.

Illustration by Anna Children Atkins. An intricate engraving featuring twenty-eight shells of varying shapes and sizes arranged in three rows. The fine details capture their unique markings, raised textures, and delicate openings. From Lamarck’s Genera of Shells, published 1823.

The New York Public Library

First book illustrated by photography

Only a year after John Herschel discovered the Cyanotype process, he introduced it to Atkins, who quickly grasped its potential for scientific illustration. Her book, Photographs of British Algae, Cyanotype Impressions, was published in 1843 and was fully illustrated—both images and text—using the Cyanotype process. Atkins created botanical photograms by placing the actual plants directly onto photosensitive paper and exposing them to light, without the need for a photographic negative.

Botanical Cyanotypes

Atkins used the Cyanotype process to record botanical specimens, and 180 years later, I find myself working with the same technique and subject matter. Of course, our aims and outcomes are wildly different—scientific illustration versus statement lampshades—but our tools, the actual process and some plants too, are much the same. Atkins’ photograms were intended for scientific illustration but her plant compositions are strikingly artistic too.

Alaria esculenta, is an edible seaweed also known as dabberlocks or badderlocks. Atkins’ picture shows the long wide frond of seaweed stretches gracefully across the image, curving to the right before sweeping back left and downward to it’s base, a tangle of root like structures. Its long, undulating form conveys a sense of natural movement, as if still swaying in the ocean currents.

Atkins’ poppies, Papaver rhoeas, are a particular favourite of mine, an elegant group of poppies with open blooms intertwined with stems bearing unopened buds. The naturally tangled arrangement of the group gives the impression of swaying in a country breeze.

Like Atkins, I like to arrange my plants and flowers to capture their natural movement and use delicate flowers such as snowdrops, crocus and poppies on silk. The fine lines and details of these flowers are beautifully captured thanks to the interplay between the diaphanous silk and the Cyanotype process.

Alaria esculenta, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1843

The New York Public Library

Papaver rhoeas, from a presentation album to Henry Dixon, 1861

Botanical Cyanotype on silk lampshade, detail, composition includes an allium flower, fern, snowdrop, poppy, honesty, grasses and a decaying dock leaf.

Photography ©Julie McMahon

Cyanotype then and now

Cyanotype technique itself hasn’t changed in 200 years, though its applications have evolved dramatically. Beginning as a new and trusted tool for scientific illustration in the mid 19th century, it became very popular in the 20th century with architects and engineers as a cheap way to reproduce their drawings and plans, also known as blueprints.

Today, artists and enthusiasts continue to push the boundaries of Cyanotype, experimenting on paper, fabrics, stone, glass, and even ceramics to create uniquely personal imagery.

There’s something wonderful about creating imagery with a process that dates back to the origins of photography. It’s a privilege to work with this technique, reimagining its use for a modern audience, not just through lampshades and art but as part of a wider community of alternative photography artisans keeping these methods alive, evolving, and relevant.